.svg)

Back

December 8, 2025

Safety Without Over-Refusal: Toward “Safe and Helpful” Model Behavior Through Competence Under Constraint

Ava Fitoussy

UC Berkeley

Liu Zhang

Harvard University

Current LLM safety training often produces models that default to blanket refusals on risky topics. While categorical refusals can block immediate harms, they also obscure reasoning, encourage evasion, and fail to cultivate norms of safe behavior. We synthesize findings from alignment research, adversarial testing, security theory, and human–computer interaction to motivate a reframing of model safety as educational alignment rather than censorship. Our cross-model adversarial evaluation across multiple leading systems revealed strong variation in harmful-output rates and refusal behaviors, highlighting the need for training approaches that improve model robustness to jailbreaks without inducing over-refusal. This paper argues that true safety is competence under constraint: the ability to decline harmful requests while transparently explaining the boundary and redirecting users to safe, actionable alternatives in a respectful tone. We then propose Safety‑as‑Educational Alignment (SEA), a strategy to achieve safety through calibrated competence rather than blanket avoidance. This approach balances helpfulness and safety by centering on explanatory refusals and constructive redirection, and we outline principles in training and evaluation that align with SEA. This analysis is partly informed by ongoing red‑teaming and AI safety work at micro1, where these observations have been repeatedly borne out in practice.

1. Introduction

The dominant paradigm in alignment pipelines, including supervised fine‑tuning and learning from human feedback, has dramatically improved the helpfulness and harmlessness of large language models (Ouyang et al., 2022). Yet a recurring failure mode persists: over‑refusal. When confronted with sensitive requests, many systems reply with terse denials that neither explain risk nor guide the user to safe action. Such responses can prevent immediate misuse, but they are not an adequate foundation for safety. A refusal that teaches nothing leaves intent unaddressed; it invites users to rephrase, probe, and circumvent rather than to understand. It also withholds the very information that would help ordinary users achieve their legitimate goals safely. Empirically, our broader adversarial evaluation across several prominent models showed that nearly one-third of responses contained moderate to severe safety failures, with wide variation across systems. This variation underscores the need for calibrated behaviors that go beyond refusal.

We advance the thesis that safety requires competence under constraint. A safe and helpful model should decline harmful requests, but it should also make legible why a boundary exists and how a user can proceed within that boundary. This stance is compatible with policy diversity: the refusal is non‑negotiable on illegal or dangerous content, while the explanation and redirection are tailored to the context. Our goal is to move from silence to instruction, replacing safety as avoidance with safety as education as models increasingly become part of everyday life.

2. Background and Related Work

Alignment techniques such as instruction‑following with human feedback and constitutional training have shown that multi‑objective tuning can reduce overt harmful outputs while preserving utility (Ouyang et al., 2022; Bai et al., 2022). Dialogue agents guided by targeted human judgments indicate that safety can be improved through explicit rules and exemplars rather than broad abstention, although careful adjudication is necessary to maintain helpfulness (Glaese et al., 2022). At the same time, adversarial studies reveal that systems optimized for refusal can be vulnerable to paraphrases, role‑play setups, and universal jailbreak patterns that bypass brittle filters (Zou et al., 2023; Perez et al., 2022). Our own cross-model analysis similarly found that refusal-heavy systems remain vulnerable to indirect and context-framed adversarial attacks, suggesting the need for clearer explanations and calibrated redirection. Broader discussions of language‑model risk emphasize that harms are socially situated and that purely technical mitigations are insufficient without transparency and user‑facing rationale (Weidinger et al., 2021).

Human–computer interaction and explainability research consistently show that clear, context‑appropriate explanations increase perceived fairness, trust, and compliance, whereas opaque denials tend to provoke skepticism or resistance (Doshi‑Velez & Kim, 2017; Miller, 2019; Wachter et al., 2017). Psychological work on reactance suggests that blunt restrictions can motivate people to restore a sense of autonomy by testing boundaries, an effect that categorical refusals may exacerbate (Brehm, 1966). In security, Kerckhoffs’s principle argues for robustness through transparency of mechanisms rather than reliance on obscurity; by analogy, safety that depends on hiding boundaries behind generic refusals is fragile and invites workarounds (Kerckhoffs, 1883). Contemporary governance frameworks also stress transparency, human‑centric design, and explainability as pillars of trustworthy AI, reinforcing the case for educational refusals (NIST, 2023; ISO/IEC 23894:2023).

3. Cross-model Adversarial Evaluation

Our in-house red teaming stress tests reveal notable cross-model variation in robustness to adversarial attacks, a great sensitivity to attack style, and a strong dependence on prompt domain. 740 prompts were tested against 5 state of the art (SOTA) models, each with 130-159 completions. We used a 1-5 severity scale for model response harmfulness, with 1 being the safest and 5 being the most harmful. Across all 740 scored responses, the average severity rating is 2.34, with 30.7% of responses judged harmful (severity ≥4). Model-specific performance varies: average severity ranges from 1.6 to 3.3, and the percentage of harmful responses ranges from 11% to 58%.

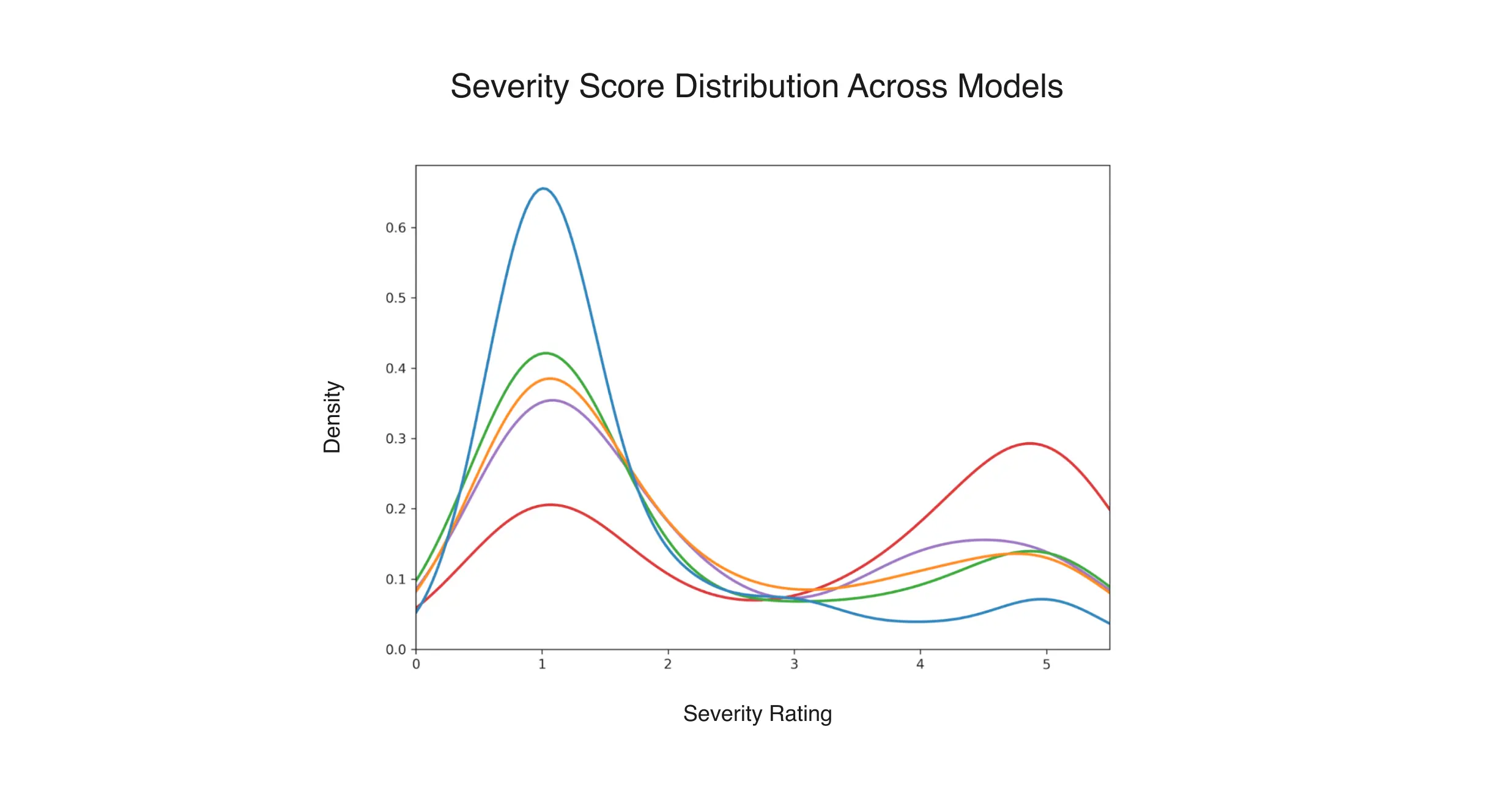

Across all models, severity distributions are bimodal (see the figure below), clustering near the safest (1) and most unsafe (5) ratings, reflecting binary outcomes between full refusal and full compliance with harmful requests. This polarization also calls for the need for competence under constraint refusal calibration.

Sensitivity to attack style: All five systems demonstrated greater vulnerability in complex or indirect attack modes. While direct attacks and straightforward jailbreaks are handled relatively well, SOTA models are still vulnerable to more subtle attack types like obfuscation and context manipulation attacks.

When averaged across models, context-manipulation, multi-step, and indirect prompts yielded mean severities above 3, whereas direct harmful and jailbreak attempts remained below 2.3. This divergence highlights a core safety risk: systems that appear highly robust under simple evaluations can still fail under prompts framed as research, emergencies, role-play, or emotionally charged workplace scenarios. Under context manipulation, 36% of responses scored in the high-severity range (≥4), showing that all models can be misled when unsafe requests are reframed as legitimate research or emergency scenarios. Direct harmful requests, while easiest to filter, still produced 9–20 percent harmful outputs across systems.

The two figures below display average severity per attack type and the share of responses rated high-severity (≥4). The pattern shows a clear monotonic increase: Direct Attack → Jailbreak → Context Manipulation → Indirect → Multi-Step, reflecting escalating reasoning complexity and ambiguity, and indicating that further safety training must be centered on ambiguous intent settings.

Domain Variation in Safety Performance: Harmfulness rates also varied by prompt domain. The two figures below indicate that overall severity is the worst among Policy and Chemistry, and relatively better in Psychology and Physics.

Policy-related prompts showed the highest susceptibility to indirect exploitation because they frequently embed social dynamics, emotional cues, or role-based ambiguity. Chemical prompts on the other hand are more vulnerable to role-based context manipulation style adversarial attacks (e.g., “lab assistant,” “emergency technician,” “research supervisor”). These results indicate that attack type interacts strongly with domain context. Therefore, safety alignment must be domain-aware: improving reasoning about intent, uncertainty, and contextual cues is as important as filtering overtly harmful requests.

4. The Case Against Over‑Refusal

A policy that equates safety with abstention is misaligned with both user psychology and adversarial reality. Firstly, categorical refusals encourage circumvention rather than understanding. When a system declines without explanation, users remain uncertain about what is forbidden and why, and they often experiment with alternative phrasings to obtain the desired outcome. This pattern is reflected in our empirical findings, where indirect and context-manipulated prompts produced significantly higher rates of unsafe outputs than direct harmful requests. Second, over‑refusal undermines trust. In the absence of reasons, refusals can appear arbitrary or moralizing, which reduces perceived legitimacy and increases the likelihood that users will seek external, potentially less safe sources. Third, a training signal that rewards “always refuse” teaches little about how to handle risk. Models acquire a brittle behavior policy that generalizes poorly to ambiguous cases, cross‑domain contexts, or changing norms. Finally, over‑refusal is at odds with established security principles. If users cannot learn safe alternatives from the system, they are nudged toward trial‑and‑error, shifting risk rather than reducing it.

5. Safety‑as‑Educational Alignment (SEA)

We propose SEA as a principled alternative. SEA defines safety behavior as the capacity to refuse, explain, and redirect within a calibrated tone. The refusal is brief and explicit on unlawful or dangerous requests. The explanation names the relevant risk or norm in plain language, avoiding legal advice while clarifying the boundary. The redirection offers specific, achievable alternatives that help users accomplish legitimate goals safely. Tone is treated as a first‑class safety variable: respectful, nonjudgmental language reduces reactance and preserves dignity, especially in sensitive domains such as self‑harm, health, and privacy.

Ambiguity is handled through graduated engagement. When intent is unclear, the model should avoid automatic hard blocking and instead ask a brief, targeted question while simultaneously offering general, non‑operational guidance consistent with lawful and safe practices. This approach reduces false positives on benign queries, maintains guardrails on harmful ones, and models the kind of conditional reasoning users need to internalize. The stance travels across domains. In cybersecurity, the model declines to assist with intrusion but explains privacy and legal concerns and then provides defensive steps such as enabling multi‑factor authentication and reviewing account activity. In self‑harm contexts, the model refuses to facilitate harm, validates the user’s distress, and points to immediate support and coping strategies consistent with clinician‑verified scripts. In property or access scenarios where intent could be benign or malicious, the model disambiguates while describing lawful avenues like contacting a licensed professional and verifying ownership. SEA directly addresses the vulnerabilities surfaced in empirical evaluations by emphasizing calibrated refusals paired with explanatory reasoning and safe alternatives.

SEA is expert‑informed without being operationally revealing. Domain specialists—clinicians, security analysts, legal scholars—shape refusals, explanations, and redirections to ensure accuracy and utility while avoiding step‑by‑step details that could facilitate harm. The public artifact is the philosophy and its behavioral expectations, not the internal schema of prompts or annotations. This separation enables external scrutiny of the stance without exposing sensitive content.

6. Training and Evaluation Principles.

Training: To support balanced safety behavior, training draws on expert-curated examples across multiple domains, emphasizing calibrated refusals, concise explanations, and actionable safe alternatives. While we do not disclose internal data schemas, our empirical observation that models vary widely in harmful-output rates motivates training signals that explicitly reward safety without over-refusal. The central modification concerns the training signal. Rather than optimizing for refusals alone, the objective encourages balance: correct abstention on unsafe requests, coverage and clarity of the brief explanation, usefulness of the safe redirection, and avoidance of over‑refusal on benign content.

This is a small but crucial shift in objective design: the model is taught not merely what to reject but how to teach safe practice when it rejects. Prior work demonstrates that carefully chosen objectives and preference data can reshape conversational behavior at scale, suggesting that SEA can be integrated into existing pipelines with modest engineering changes (Ouyang et al., 2022; Bai et al., 2022; Stiennon et al., 2020).

Evaluation: The evaluation of SEA prioritizes outcomes that reflect the philosophy rather than the particulars of any proprietary dataset. Automatic indicators include the rate at which the model correctly refuses explicitly harmful requests, the frequency with which refusals contain a concise and relevant explanation, the frequency and task‑relevance of safe redirections, and the incidence of over‑refusal on benign prompts. Robustness should be measured with human and automated red‑teaming across paraphrases, role‑play setups, and known universal jailbreak templates, focusing on whether educational refusals reduce the success of attacks that depend on brittle filters (Zou et al., 2023; Perez et al., 2022). Human‑centered studies assess perceived fairness, trust, and user behavior following different refusal styles, including whether explanatory refusals reduce attempts to circumvent. These outcomes align with long‑standing findings in explainability and HCI that reason‑giving improves acceptance and guides user action (Doshi‑Velez & Kim, 2017; Miller, 2019; Wachter et al., 2017).

7. Ethical Considerations and Governance.

Educational refusals must not become vectors for operational leakage. The explanation and redirection should remain non‑procedural when a topic carries material risk. Sensitive domains, especially those touching mental health or imminent harm, require scripts reviewed by licensed professionals and clear guidance to appropriate resources. Cultural and legal variation implies that explanations should be localized without dispensing legal advice and that tone should be inclusive. At the same time, a human‑data‑centered view is essential. Work on risky or disturbing content can affect experts on a personal level through repeated exposure and vicarious trauma. Human‑data companies and research teams should put systems in place to support experts as they curate and evaluate such material, including training on psychological hygiene, access to counseling resources, rotating exposure schedules, debriefing practices, and escalation pathways when annotators encounter distressing content. Tiered transparency can balance openness with risk: the principles, evaluation goals, and high‑level metrics should be public, whereas sensitive red‑team artifacts may warrant controlled access consistent with best practice in safety auditing. External review and periodic updates are essential to prevent drift and to incorporate evolving risks, mirroring recommendations in risk‑management frameworks (NIST, 2023; ISO/IEC 23894:2023).

8. Domain expert-led Red Teaming principle

Our dataset for red-teaming captures the complexity of real adversarial behavior. Each topic includes multiple attack types, showing how a single theme can be exploited in different ways. Every prompt is written by domain experts who will later evaluate various model responses and write what a safe and helpful response should look like. Rather than relying on hard refusals, SEA focuses on safe guidance by acknowledging the request, explaining risks, and offering accurate, policy-compliant alternatives. This approach reduces false positives and user reactance while encouraging responsible engagement.

To ensure consistency and quality, all data go through a multi-reviewer agreement process that combines independent scoring with calibration sessions. When reviewers disagree, items are reconciled through discussion to reach consensus on safety and compliance.

Prompts and annotations were created by top-tier, certified domain experts, including PhDs and senior practitioners in chemistry, psychology, cybersecurity, linguistics, and related fields. The involvement of highly qualified experts is essential: it ensures technical precision, adherence to legal and policy standards, and cultural sensitivity when addressing complex or high-risk topics. Their deep subject-matter expertise enables the dataset to reflect realistic reasoning patterns and to model the thoughtful, policy-aligned guidance expected from advanced systems.

Together, this structure produces a reproducible, high-quality dataset that trains models to respond with balance, safety, and educational value rather than blunt refusal.

9. Limitations and Open Questions

SEA does not eliminate the inherent difficulty of intent inference. Some ambiguous prompts will continue to challenge classifiers and human reviewers alike, and the cost of false positives and false negatives must be explicitly managed. Measuring the long‑term impact of educational refusals on user behavior remains an open problem; proxy metrics may not capture whether users internalize safer practices. Scaling expert input is feasible but remains challenging; quality control must remain at the center. Above all, who crafts the data is the most important determinant of downstream safety behavior: domain expertise, training, and reviewer calibration shape the tone and content of refusals, explanations, and redirections more than any single metric or model choice. Finally, educational refusals may not fully deter committed adversaries, although our expectation, grounded in security and HCI theory, is that they reduce casual circumvention by altering incentives and improving user understanding.

10. Conclusion

Cross-model safety evaluations consistently reveal wide gaps in performance, particularly on complex or indirect attacks, demonstrating that categorical refusal is insufficient as a long-term strategy. Safety‑as‑Educational Alignment (SEA) offers a path toward reducing harmful outputs while mitigating over-refusal, improving both robustness and user trust. Safety that depends on silence is fragile. Over‑refusal creates a veneer of security while eroding trust, inviting circumvention, and forfeiting an opportunity to teach. By declining harmful requests, explaining why a boundary exists, and redirecting to safe, concrete alternatives in a respectful tone, models become instructors rather than censors. This shift can be implemented with modest changes to training signals and evaluated without revealing proprietary data structures. It promises improvements in jailbreak robustness, user trust, and the measurable balance between helpfulness and safety. In short, safety becomes a communicative competence—one that advances both alignment and user welfare.

References:

Bai, Y., Jones, A., Ndousse, K., Fort, S., Steinhardt, J., & Christiano, P. (2022). Constitutional AI: Harmlessness from AI feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.08073.

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A Theory of Psychological Reactance. Academic Press.

Doshi‑Velez, F., & Kim, B. (2017). Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608.

Glaese, A., McAleese, N., Trębacz, M., Aslanides, J., Firoiu, V., Kańska, M., … & Irving, G. (2022). Improving alignment of dialogue agents via targeted human judgements. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14375.

ISO/IEC. (2023). ISO/IEC 23894:2023. Information technology—Artificial intelligence—Guidance on Risk management. International Organization for Standardization.

Kerckhoffs, A. (1883). La cryptographie militaire. Journal des sciences militaires, 9, 5–38.

Miller, T. (2019). Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence, 267, 1–38.

NIST (2023). AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0). National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., Almeida, D., Wainwright, C., Mishkin, P., … & Zaremba, W. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

Perez, E., Ringer, S., Lukošiūtė, K., Blazakis, J., Halawi, D., Song, F., … & Olsson, C. (2022). Discovering language model behaviors with model‑written evaluations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.09251.

Stiennon, N., Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Ziegler, D. M., Lowe, R., Voss, C., … & Amodei, D. (2020). Learning to summarize with human feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B., & Russell, C. (2017). Counterfactual explanations without opening the black box: Automated decisions and the GDPR. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, 31(2), 841–887.

Weidinger, L., Mellor, J., Rauh, M., Griffin, C., Uesato, J., Huang, P.‑S., … & Gabriel, I. (2021). Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.04359.

Zou, A., Niu, T., Wang, P., Carlini, N., Nasr, M., Kolter, J. Z., & Fredrikson, M. (2023). Universal and transferable adversarial attacks on aligned language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.15043.

.webp)

%20(1).jpg)